Who We Are

What We Support

Sharing Our Work

Stories of Impact

Copenhagen has always felt like a place that teaches — not through lectures, but through the way it’s built.

I first came to the city in 2024 as part of the Scan Design Interdisciplinary Ecological Design Study Tour and Studio at the University of Washington. The study tour was packed with excursions to real-world projects showcasing Copenhagen’s approach to climate resilience and well-being. We visited firms like BIG, COBE, SLA, and Schulze + Grassov and saw projects that have become icons of Danish design. Between visits, we racked up countless miles biking through the city, just like the Danes.

Now, with the continued support of the Scan Design Foundation, I’m back for the autumn term, interning with the urban design firm Schulze + Grassov. As a recent graduate of the Masters in Urban Design and Planning program from UW, I feel fortunate to learn not only from urban designers, architects, and landscape architects in a collaborative office setting, but also from the city itself — one internationally recognized for its high quality of life, vibrant public spaces, and endless cultural and design-related events.

This year’s inaugural Copenhagen Architecture Biennial was a highlight of the season. Its theme, Slow Down, explored how architecture can help us decelerate our overheated sites, cities, and societies. Over the course of a month, more than 150 events invited people of all disciplines, ages, and abilities to experience architecture through film, lectures, exhibitions, and workshops. Eager to learn more about the intersection of architecture, urban design, and well-being, I attended ten of them.

The first was the film Mon Oncle, introduced by Jan Gehl, one of Denmark’s most influential urban designers and architects. I first learned about Gehl in my Introduction to Urban Design class at the University of Washington, where his focus on how people use and experience public space further shaped how I think about design.

As Gehl explained, Mon Oncle is a playful critique of modernism — a film that portrays modernity as unnecessary, even frivolous, with its gadgets and aesthetics often serving more for show than for function. It was a humorous but poignant reminder of how design can drift away from human needs and contribute to social inequities. Gehl described the film as one of his early inspirations, setting the tone for his life’s work of designing with people in mind.

A week later, I attended a second Gehl presentation featuring The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces by William H. Whyte. This uplifting look at how people behave in public spaces reaffirmed that even the smallest design decisions can profoundly shape social life in cities. Having first seen this film in my urban design class as well, I remembered how captivated I was by some of the film's observations in public space. Fast forward a year later, I’ve now participated in pedestrian counts and public life observations in Copenhagen’s city center.

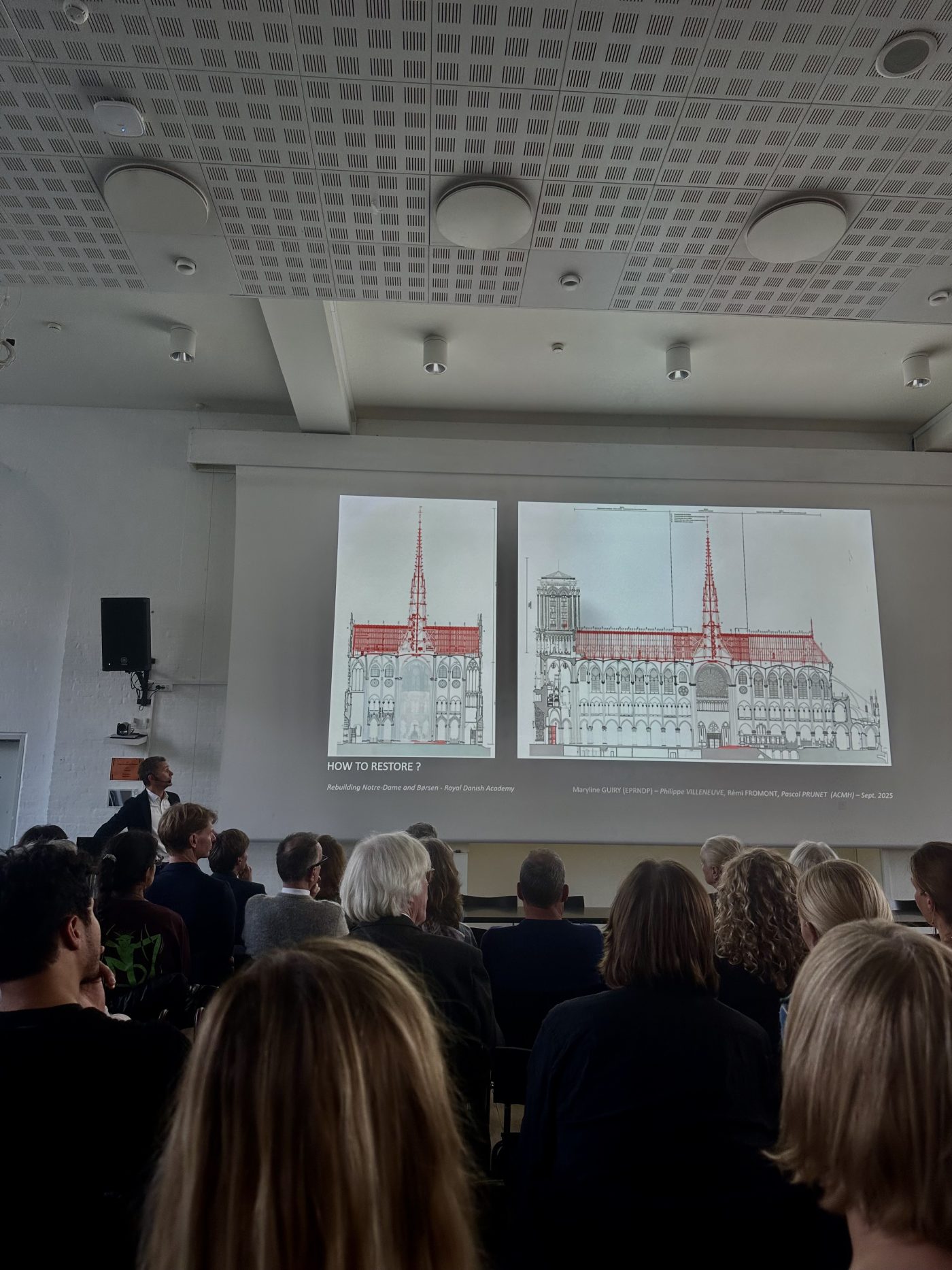

The Biennial also offered global perspectives on architecture. One memorable event highlighted a French-Danish collaboration between architects working on the reconstruction of two cultural landmarks, Notre Dame in Paris and Børsen in Copenhagen, both damaged by fire in recent years. Listening to how each team balanced preservation with contemporary sustainability challenges revealed how architecture serves as a bridge between history, culture, and the future.

Another event hosted by Architects Without Borders showcased student projects that looked at how architecture could provide social and infrastructural solutions to different communities across the world. One student looked at how shared spaces could be adapted and designed for the needs of specific social groups, in this case Muslim women in rural areas. Another group considered accessibility and sensory needs in a housing project. Both projects really centered the end-user experience in their designs, making decisions based on how the outcomes could aid people’s daily lives, ensuring that their work was both functional and culturally-responsive.

The final event I attended was the screening of Making Materials Matter, a documentary about Danish architect Søren Pihlmann and his work rethinking how we build. At first glance, construction materials might seem mundane, but the film turned them into something poetic. Pihlmann shows how reusing existing materials, no matter how small or imperfect, can transform both the industry and our relationship with the environment.

It was a fitting way to conclude my Biennial experience, reminding me to slow down, look up, and rethink how we design and build. As I continue my work in Copenhagen, I carry these lessons forward – to design with empathy, to listen to the city and its people, to see the value in the small things, and to remember that slowing down is often the best way to move ahead.

Author Bio: Rebecca Zaragoza Tejas is from the Eastern Coachella Valley in California. She is currently an urban design intern at Schulze + Grassov in Copenhagen, Denmark. She recently earned her Master of Urban Design and Planning from the University of Washington (UW), where she specialized in landscape and urban design.

Rebecca T. Zaragoza

Master of Urban Planning Candidate